The 1980s Color Fields of John Opper

With his first solo show “Harmonies” with Berry Campbell Gallery, John Opper’s (1908-1994) late-career work is presented in new light as one of the leading colorists of the New York School. Featuring 19 paintings predominately from the 1980s, the exhibition aims to elevate Opper to a new level of both scholarly and commercial acclaim.

Born in Chicago, Opper became interested in Modernism after a visit to the Pittsburgh International Exposition in 1928, where he first discovered the works of work of Picasso, Matisse, Braque, and other abstract painters. He studied at the Cleveland School of Art, and later took classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. He quickly befriended Hans Hofmann after moving to Gloucester, Massachusetts, and joined the WPA Easel Division in the 1930s. Opper stated that he credited the WPA experience with introducing him to a modern way of creating.

After his time with the WPA Opper fully left behind nature and the physical world, and pivoted to pure abstraction. Like many artists of his generation, leaving behind any sense of figure or narrative was initially derided by critics and collectors, but nevertheless, they moved forward with their work. As much as we understand the abstract in the 21st century, it was a very radical departure for many at the time, and wasn’t fully appreciated until the 1950s. Later in New York, he painted at Milton Avery’s studio in New York, and became acquainted with Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko. After leaving the city, he would frequently come back to spend time at the Cedar Bar associating with Franz Kline, Philip Guston, and Willem de Kooning.

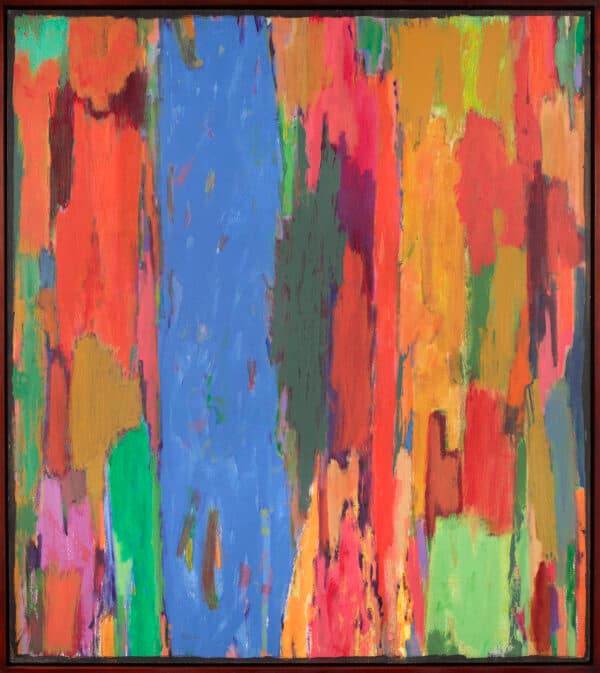

After a heart attack in 1966, he permanently switched from oil-based paint to acrylic, which despite being a necessity for his health, opened a lot of creative doors for him. The closest visual comparison to Opper’s work would by Helen Frankenthaler, but unlike her thinly stained canvases, his work is heavily painted and are much deeper tones. They maintain the look of stain, but with the acrylic paint Opper was able to create multiple layers of multi-tonal colors, which really make his work shine. The overall muted colors appear to be a direct rebuttal against the brighter colors in nature, while always retaining the natural balance that is specifically from the natural world. His canvases are not drips, and they’re not allover, but they are certainly abstract expressionist by definition.

© Estate of John Opper. Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York.

The next comparison to be made would have to be Clyfford Still. Their forms have strong similarities, but Opper’s work is more condensed, therefore being able to work with a larger array of color and shapes. Opper creates flat works with no fore or background at all, generating balance and tension through the use of color instead of any geometrically based abstraction. Joan Mitchell’s work could also be an influence, but there is far more focus and potential energy in Opper’s work. They are comfortably dense in execution, but like a map of Pangea, one can feel the possibility of colorful explosion that is appearing right before our eyes. There is strong composition and color, but these late works are a perfect example of the right amount of restraint being used by an experienced hand.

In these 1980s works, they appear to be more intuitive and less planned out than his early works that built upon the work of Picasso, Rothko, and Matisse. It is here where he’s going out into unfamiliar territory and creating something art-historically important. Many artists who achieved a ton of fame early often rest on their laurels and stagnate, as it’s often easier to continue with something successful instead of trying something new that your patrons and critics may not like. Opper on the other hand continued to push and experiment to develop his mature style, and thankfully for the viewer, he eventually got there once he let go of what others were doing and fully immersed himself into his own world.

© Estate of John Opper. Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York.

The Standout painting is most certainly the massive 1990 work “Cleveland” that is about 5 x 10 feet in size. From his entire oeuvre, and certainly the presentation in “Harmonies”, it’s clear that, like a fine wine, Opper continued to get better with age. Controlled color, a small glimpse of light shining through the surface, and effortlessly sleek looking surfaces make for a very satisfying yet challenging work that should be given plenty of time to fully embrace. Other artists might have achieved more fame in their lifetime, but Opper’s work still has a lot of story left to tell.

Berry Campbell Gallery, run by the warm and knowledgeable gallerists Christine Berry and Martha Campbell since 2013, is known to the art world for representing some of the best Post-War abstract artists – including Dan Christensen, Stephen Pace, and Susan Vecsey – that received some early fame, but never fully received the level of praise their work should have garnered throughout their early to mid-career. Opper is another beacon of hope being presented in a new light, one that that he should have received far earlier in his career. Make sure to go check it out before December 23rd.