Artist Q&A with David Carbone

David Carbone, Professor Emeritus of Painting and Drawing in the Department of Art and Art History, University at Albany, SUNY, received his B.F.A. at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts/Tufts University. He also spent a summer in Maine at the Skowhegan School, and later, earned his M.F.A. at Brooklyn College. He has studied with T. Lux Feininger, Henry Schwartz, Jan Cox, Barnet Rubinstein, Gabriel Laderman, Lee Bontecou, Jacob Lawrence, Jimmy Ernst, Carl Holty, Harry Holtzman, Joseph Groell, Philip Pearlstein, Alfred Russell, and Sylvia Stone. Carbone has had seven one-person exhibitions including shows at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, Zoe Gallery, Boston, David Brown Gallery, Provincetown, and Hackett-Freedman Gallery, San Francisco. He is a painter, critic, and curator living in New York City. He has shown his work across the country and written for various print and online publications.

Who is your favorite artist of all time?

Really, is there anything duller than an artist talking about their love of a famous artist—we all know too well: Leonardo, Piero, or Vermeer! Yes, they are all worthy. Perhaps, having a favorite artist may even be dangerous? Often, it points to a limited experience of art or worse to a limited capacity to respond to the varieties of human experience. For me, much of the value of a life in art is found in a conversation between works of art. Art, even when it is buoyant and joyous, is a matter of contemplation and meditation; I always look toward what is hidden in plain sight.

How did you become a professional artist?

Did I have a choice? Not that my parents wanted me to become an artist; it isn’t an easy career by any means. I grew up with bohemian parents who traveled in artistic circles. My father was a sculptor and my mother spoke several languages with a keen interest in poetry. As an only child of often absent working parents, I was left to my own devices, which led me to draw. Being left alone is an important experience; it allowed me to discover the wonder of things. Drawing, like writing, is a way of knowing what I feel, what matters to me.

What are the influences and inspirations in your work?

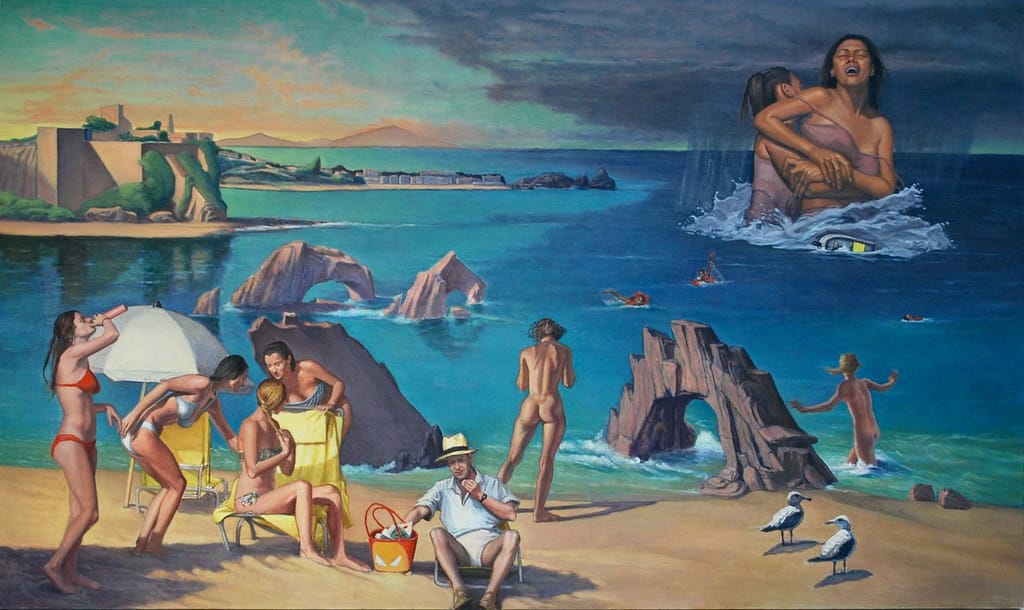

A group of four works are politically inspired: Inherent Anxieties, The Age Old Paradox, The Sacrifice of the Archaeologist Khaled al-Assad, and Neither Out Far Nor in Deep, all reference the current conflict in Syria. In the first work, there is a contrast between privileged Americans’ petty betrayals and the profound devastation of the Syrian people. In the second painting, there is the bitter paradox of the “Good Shepherd”, claiming to be protective, but always seeking sacrifice. This work is also my way of honoring the “White Helmets”, the men who stayed behind to rescue people after the Russian bombings of Syrian cities like Aleppo. In the third work, I pay homage to Khaled al-Assad, archaeologist and head of antiquities for Palmyra, who stayed behind to face members of ISIS and stand for his life’s work, the irreplaceable treasure that was Palmyra, the first great city of cultural diversity. And finally, the fourth painting, completed during New York’s pandemic lockdown, depicts the spectre of refugees in peril at sea, set against the indifference of our western tourist culture. The title is borrowed from a poem, by Robert Frost, which resonates for me with the painting.

How is your work different than everything else out there?

I take a great deal of pleasure in the various works of others. As for my paintings, they must have a certain strangeness or they would bore me and become tedious. I want my paintings to be a waking version of nocturnal life, where even the most ordinary scene is a synthesis of things and myself. When I paint an object, I have the sensation of entering it, as if it were a shell. My frequent mixing of disparate pictorial form treatments has become essential; realism, by itself, seems unable to transmute my thought into art.

When is a piece finished for you?

Perhaps the question should be when is the work finished with the artist? Making a new work is always an adventure filled with uncertainty that calls into question all that I know. Often, I feel like a medium through whom an unknown quality may appear: the spirit of the work itself, called into material form.

What’s different about your current body of work?

My previous work focused on vaudeville and circus sideshow subjects as a vehicle to point to the same long standing social-political-cultural issues that I’m moved by today. I’ve always been drawn into the drama of the shifting self, our paradoxical individuality. An event or dilemma in a person’s life is often the initial point of departure for a new painting. I continually return to images of an “underworld”—the Petrified Forest or the Painted Desert—landscapes that evoke a kind of psychic interior—indirectly inspired by reading Ovid and Dante.

Tell us about a few of your career highlights or moments that have greatly affected your career?

My first thought is whenever I see my work in a space that is not my studio—a gallery, a museum or someone’s home—shocked and elated. I remain indebted to the journalist John Laider who wrote a feature article on me for the Cambridge Chronicle when I was unknown and living and working in a tiny studio apartment in Cambridge. To the late Gillian Levine and now Whitney curator Elizabeth Sussman, I will always be grateful for their visit to my studio where they chose work for their ICA exhibition, Boston Now: Figuration, being included opened the doors to visibility. I’ll always remember a visit to my studio by the French art dealer Michel Soskine, then of Paris’ Galerie Claude Bernard, who bought my latest painting and insisted that I wrap it, then and there, so he could take it with him. The late writer and actor David Rakoff once put author Rachel Adams onto my work which resulted in a painting of mine becoming the cover of her book ‘Sideshow, U.S.A.’ Her book’s analysis matches my own take on how the sideshow mirrored American social and political bias, especially on race, gender and immigration. This is how my earlier work relates to my present work too. Perhaps my greatest highlights have come from poets. It was John Yau, that most perceptive and generous of contemporary art critics, once a panelist at Boston’s ICA, who included me for the Englehard Foundation Award. When I was granted an Ingram-Merrill Award—acknowledgement from the likes of James Merrill, John Hollander, John Ashbery, and J.D. McClatchy—my feet didn’t touch the ground for days.

What’s coming up for you?

I am excited to be included in Robert Curcio’s exhibition, Tales of Adjusted Desire at Robert Berry Gallery. It has given me the opportunity to show a few works from when my recent work began; they still carry a visceral shock. Also just out is my painting ‘The Cave of Making’ as the cover for Albin Zak’s Three Fantasies for Piano Solo performed by Victoria von Arx.

What advice would you give to an artist just starting out today?

Making art over the long run takes courage and resolve. At some point you may have to choose between having good taste or being human. If you are overly receptive to what the art market wants from you, your true gifts may be gradually discarded for a false set of values. Many artists have seen their creative impulses destroyed by either a lack of affirmation, or just as commonly, being trapped by success. This is the tragedy of a career in art.

Who are some of your favorite under appreciated artists that you don’t think get enough attention?

Adriaen Brouwer, a true painter’s painter, collected in depth by Rembrandt, Rubens and Van Dyck. He was the bridge between Bruegel and Dutch Tavern scenes, a true master of painterly expression, composition and above all a master of depicting human behavior. His work forecasts aspects of the Le Nain brothers and of Watteau. He made the fatal mistake of taking a studio next to an ammunitions depot. The largest collection of his work is in Munich at the Alte Pinakothek.

Alfred Russell was a key figure in the art worlds of New York and Paris, whose abstract paintings and drawingsproduced a cosmic sense of oceanic wonder. In the early fifties, he saw the business of art eating into the creative imagination of his generation and walked away from the gallery world to preserve his sense of self. Although long overlooked, his work can be seen to have influenced his friend Philip Guston’s early abstractions, as well as the early works of Joan Mitchell and Al Held. From September 1, 2022 to December 4, 2022, the Grey Art Gallery at NYU will present Americans in Paris, Artists Working in France, 1946-1962, curated by Debra Bricker Balken and Lynn Gumpert, which will feature two works by the maverick mid-century abstractionist. His work is in the Whitney Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Detroit Institute of Art.

To learn more about David and his work, please visit DavidCarbone.net.